Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

This is the first of a series of articles about Winnipeg’s sewage issues — and possible solutions.

Two or three times a week, when the weather’s nice, retired teacher Dave Taylor picks one of the three boats — a red European kayak, one steel and one fiberglass canoe — from the rack attached to the side of a shed in his yard. If he’s kayaking, he’ll load it onto a golf cart, otherwise he’ll hoist the boat on his shoulders and make a short portage across the road, through the soccer field, a small patch of riparian forest and down the muddy bank to a little pallet dock on the Red River in Winnipeg. Most days he’ll paddle a few kilometres upstream. Other days he’ll strap the boat to the car and paddle a nearby tributary like the Seine or La Salle, or take his family out on the Winnipeg River. He’s navigated the rugged Berens, Bloodvein and Pigeon rivers and paddled on the unpredictable Lake Winnipeg.

But when he’s on the Red — the river he’s lived along all his life — he does everything he can to avoid touching the water.

That’s because Taylor, like many Winnipeggers, is conscious of one of the waterway’s more unpleasant traits: it’s full of crap. Literally.

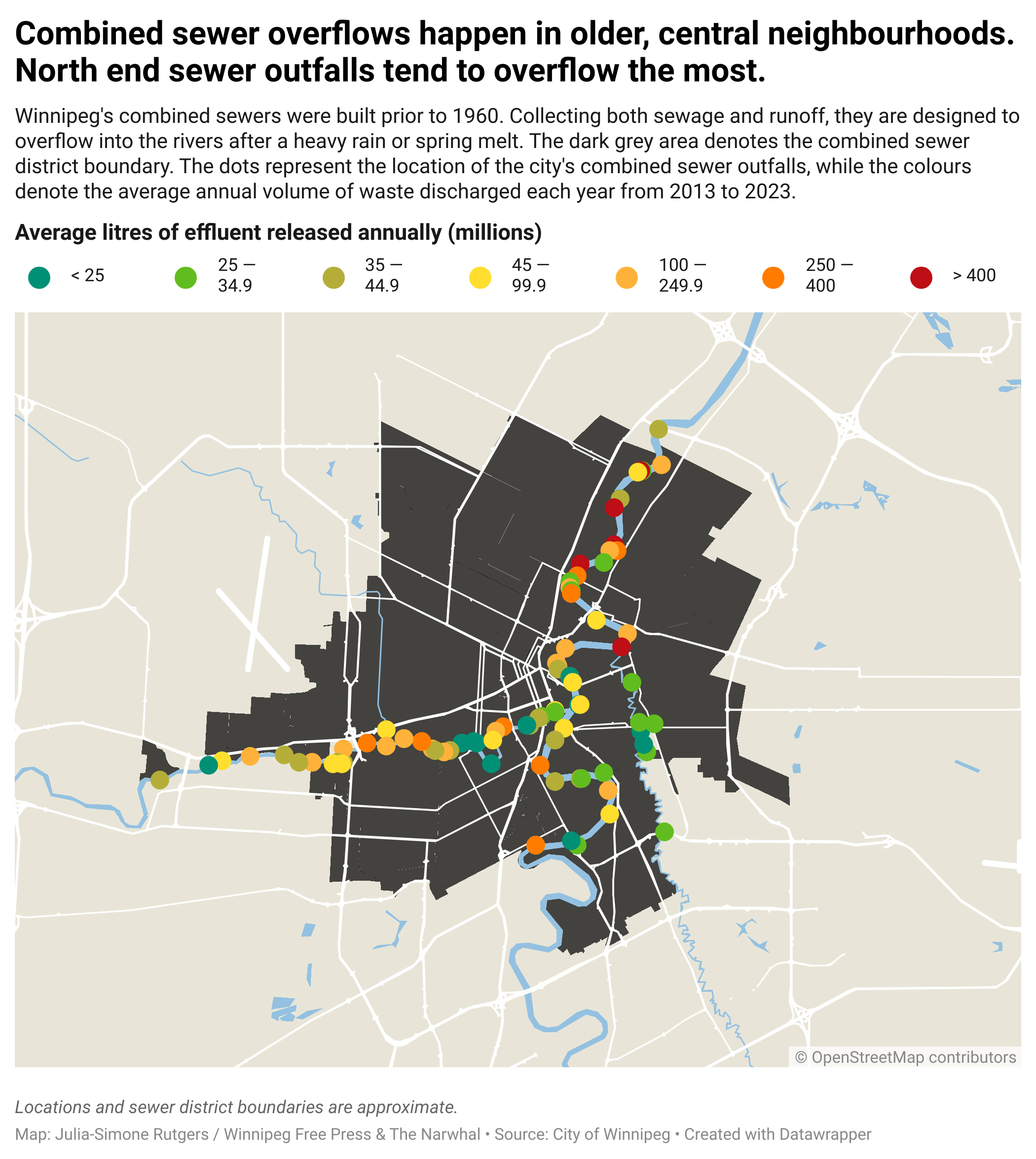

The meandering rivers — the Red and Assiniboine — that have defined and shaped Manitoba’s capital city have long served as the backstop for its sewage system. During heavy rains and big spring melts, about one-third of the city’s pipes discharge diluted raw sewage — a mix of storm water and the stuff we flush down our drains and toilets — directly into the waterways. During power and pipe failures, the rivers serve as toilet bowls, flushing the wastewater away.

Between 2013 and 2023, the city dumped 115 billion litres of sewage into its river system, according to a Narwhal and Winnipeg Free Press analysis of publicly available sewer monitoring data. That’s enough to fill nearly 46,000 Olympic swimming pools.

With climate change projected to bring more intense rainstorms, flash floods and temperature swings to Prairie cities like Winnipeg, those overflows threaten to become a more frequent affair.

Reworking sewer infrastructure is expensive. The city believes it will take until 2095 — 70 years — to stop the leaks. In the meantime, it argues in documents the impact of these combined sewer overflows are relatively minimal: they’re an eyesore, they’re unpleasant, more often than not they breach water quality regulations — but the city says they have little impact on human or aquatic ecosystem health.

“It leaves you with a bad taste in your mouth,” Taylor says of the city’s hesitation to act. “I want to immerse myself in the ecosystem and paddle it and not be afraid of the water.”

Taylor has kept a keen eye on the city’s water pollution for several decades. In the late ‘80s, as public and regulatory attention started to turn to the water quality in the Red River, he did a bit of digging, requested data from a cross-border task force and found the water he loved to paddle was swimming with diseases.

In a 1992 letter to the editor published in the Winnipeg Free Press, he wrote:

“Our rivers are putrid and include 10 pathogenic organisms which are responsible for the following diseases: salmonella, dysentery, ear infection, dermatitis, respiratory infections, gastroenteritis and polio.”

The last one hit close to home. Taylor’s mother, now 90, has spent her life navigating the impacts of a polio infection she contracted in Saskatchewan in the 1950s.

“It really struck me that these pathogens were in the river,” Taylor says, sitting at his kitchen table in the Wildwood neighbourhood, where he can occasionally catch a glimpse of the muddy brown-green river through the still-bare spring trees. “I was outraged, really.”

Three years before that letter to the editor, the Manitoba government had introduced its new Environment Act, which came with regulations meant to stem the flow of excrement into the province’s lush network of lakes and rivers. It was the beginning of a now 30-year effort to halt the damage the city has historically inflicted on waterways that Taylor calls “the heart of the city.”

For thousands of years, the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, called the forks, has been a gathering place for Indigenous nations, fur traders, railway builders and settlers.

The city was founded around the forks, and takes its name from the Cree words “win,” meaning “muddy” and “nippee,” meaning “water” — an apt description for the murky prairie rivers.

As the city grew around this pulsing heartbeat, its first sewage network was designed to back onto the water. At the time, the wastewater flushed out of homes, businesses and industrial buildings, and the runoff that flows into the city’s storm drains during melts and rainfalls were collected in the same web of subterranean pipes and emptied directly into the rivers. These pipes, mostly clustered in older centralized neighbourhoods, are known as “combined sewers,” referencing the fact they collect and transport both storm drain runoff and “sanitary sewage” — another term for wastewater carried from toilets, sinks, dishwashers, showers and other indoor plumbing fixtures.

That practice continued until the development of the North End Water Pollution Control Centre in 1937, which was accompanied by weirs that steered effluent from the combined sewer back to the sewage treatment plant. (Most neighbourhoods built after 1960 use a separated sewer system, which sends all sanitary sewage to the treatment centre, while land drainage is released into the river or into retention ponds.)

The approximately 1,000 kilometres of combined sewer pipes are a maze of complex, almost miraculous engineering. Many of the pipes are so large they could comfortably house an elephant, and can fill an Olympic swimming pool with water — or sewage — every four minutes.

Usually that’s enough capacity to handle the city’s wastewater and a light rainfall or a mild melt, but during heavy rainfalls, rapid spring melts and other days where runoff surges, even those massive pipes can be overwhelmed.

“When the volumes get too big, you either have to dump it into people’s basements — up through their toilets — or the safety valve becomes the river,” Winnipeg city councillor Brian Mayes says in a late April interview.

“Politically that was a choice made somewhere along the way: we’re going to dump it in the river.”

Mayes didn’t know much about sewer overflows before he became the St. Vital councillor in 2011. A few years later, he was chair of the city’s water and waste committee — and easily the most vocal insider critic of the sewer problems.

“It is an environmental problem,” he says. “It’s also disgusting. It’s maybe not as bad as an oil spill or something, but it’s still bad. It’s still an environmental concern.”

Between 2013 and 2023, Winnipeg’s 76 sewer outfalls overflowed a combined average of 1,300 times per year. Each outfall overflowed an average 15 times per year. Each spill dumps nearly eight million litres of diluted wastewater — a blend of runoff and sewage — into the river system, for an average total of more than 10 billion litres every year. That’s not counting the extra 14 million litres flushed annually as a result of accidents and equipment failure.

Each spill — whether accidental or by design — not only causes a surge in the list of pathogens that worry Taylor, they also increase concentrations of phosphorus and ammonia, and litter the waterways with unsightly debris — wads of soggy toilet paper, tampon applicators, cigarette butts and discarded napkins that find their way into the storm drains.

Water sampling on the Red and Assiniboine rivers shows the concentrations of suspended solids, phosphorus and escherichia coli (E. coli) nearly always exceed provincial standards after a sewer overflow. E. coli levels in particular can rise above three million units per 100mL. The provincial guideline during an overflow is 1,000 per 100mL. The federal guideline for safe swimming is 235 units per 100 mL.

According to the United States’ Environmental Protection Agency, which has developed a gold-standard policy document for sewer management, overflows “are a major water pollution and public health concern.”

And yet, Mayes has spent years trying to convince his colleagues it’s a problem worth solving. His frustration boiled over as the water and waste committee debated funding for the program at a meeting in April and he quipped “I don’t know why I waste my time, but I do.” (It’s a comment he looks back on with regret.)

Winnipeg city hall has taken the position that the rivers are big enough to dilute the toxins in sewage overflows, and murky and fast-moving enough to discourage swimming, waterskiing and other water sports so the risks are minimal — at least if you weigh up the costs.

It’s not that council doesn’t care, Mayes says. But upgrading sewage infrastructure is an expensive and disruptive process, and there are far more pressing water pollution problems to tackle first. The 90-year-old North End sewage treatment plant, for example, is in dire need of upgrades, currently pegged at $3 billion, to significantly curb phosphorus pollution and keep pace with the city’s growth.

But Mayes hasn’t given up.

“You can walk and chew gum at the same time,” he says. “We should also care about this.”

Mayes isn’t the first to try and urge the city to act on sewer overflows. Taylor has now spent decades penning opinion articles and letters to the editor, reaching out to political leaders and even once showing up at a presentation of the International Joint Commission — the Canada-U.S. coalition studying water quality problems on the Red River in the early 1990s — with glasses of river water to present to panelists, in an effort to convince the city to take action.

“It’s been stagnant,” he says. “The movement toward fixing these things — it’s just not happening.”

In 1992, Manitoba’s Clean Environment Commission found combined sewer overflows contributed to water quality concerns on the Red and Assiniboine rivers, but there wasn’t enough data to fully understand the impacts. The commission recommended the city study overflow impacts, notify the public of sewage releases and get to work on a master plan to reduce the frequency.

Winnipeg spent ten years on the overflow study and eventually concluded: “[Combined sewer overflow] control will be costly and the benefits are subjective.” The plan, then, would be to chip away at sewer upgrades for 60 years to eventually bring the annual number of overflows down from an average of about 18 overflow events per year to four in the peak season for water recreation.

The city presented these findings to the commission at a second round of hearings in 2003 — just months after the worst spill in Winnipeg history sent more than 400 million litres of sewage into the Red in a 57-hour span. The commission found the city’s plan lacking.

“Winnipeg’s treated municipal wastewaters and untreated combined sewer overflows are adversely impacting the aquatic environments of the Red and Assiniboine rivers and Lake Winnipeg,” the commission, chaired by current federal Environment and Climate Change Minister Terry Duguid, wrote in the final report.

“People living along the Red River downstream from the City of Winnipeg commented that they know when there has been a sewage release or combined sewer overflow by the odours and floating debris. They mentioned that they have to cease activities near the river, clean up their equipment and wash their clothes.”

Winnipeg would need to halve the timeline to complete its plan and start taking immediate action to reduce overflows. The commission was optimistic the city could make “meaningful progress” within two years.

But sewer overflows are as unsexy an issue as a city council can raise. For years, money earmarked for sewer upgrades was diverted into municipal coffers to fund tax freezes, while the out-of-sight, out-of-mind infrastructure kept leaking. A handful of projects — better data collection tools, three sewer separation projects, a cleanup at one particularly messy sewer — were completed in the interim, but work toward a formal overflow plan didn’t start until the provincial government made it a condition of an Environment Act licence issued in 2013.

The master plan first recommended in 1992 was finally completed in 2019.

The roadmap within is an echo of the plan presented to the Clean Environment Commission in the early aughts: the city will chip away at upgrades to capture 85 per cent of sewer flow (compared to 74 per cent in the baseline year 2013) at an estimated cost of $2 billion (in 2019 dollars). The plan would effectively cut overflow volumes in half. With financial support from other levels of government, the work could be done “close to 2045,” the plan says. If the city goes it alone — as it’s done so far — it will take the better part of 70 years, with a target completion date somewhere in 2095.

“It will take a long time to do it, but it shouldn’t take 70 years,” Mayes says, exasperated.

“Other cities are dealing with this. I think we should certainly be picking up the pace.”

In the meantime, the communities and waterways downstream will have to carry the burden — and the cumulative impacts could be devastating.

When Winnipeggers were asked what concerned them most about sewer overflows in 2015, the health of the province’s crown jewel — Lake Winnipeg — ranked top of the list.

It’s the last stop on the Red River’s meandering journey north from the Minnesota-North Dakota border; it’s the sixth-largest lake in Canada, 11th largest in the world; and in 2013, Lake Winnipeg earned the dismal accolade of “most threatened lake of the year.”

Algal blooms have shuttered beaches and popular fishing holes as the water turns slime green and dangerous to touch. The lake’s once booming fish populations have been strained by cumulative challenges, forcing several fisheries to close up shop.

According to research conducted by the International Institute for Sustainable Development and the Lake Winnipeg Foundation, this decline is mostly caused by phosphorus. “We have 50 years of data on multiple whole lake ecosystems, various nutrients have been tested and repeatedly those experiments have demonstrated that algal blooms are caused by excess phosphorus,” Lake Winnipeg Foundation executive director Alexis Kanu says in an interview. “You can effectively control algal blooms and reduce their prevalence by reducing inputs of phosphorus.”

The North End sewage treatment plant is the largest point source of Lake Winnipeg’s phosphorus overload — hence the urgency to tackle billions of dollars worth of outstanding upgrades. Sewer overflows, by contrast, contribute very little to the overall phosphorus picture on the lake.

“This is going to sound funny to say because we hear these horribly large amounts of raw sewage being discharged into our rivers … but daily, all the sewage that we send through the treatment plant dwarfs what’s being released from the combined sewer overflows,” Kanu says.

According to the foundation’s analysis, sewer overflows are responsible for less than 0.5 per cent of the lakes’ total phosphorus load, while the treatment plants account for about five per cent.

Still, according to Dimple Roy, water management director at the International Institute for Sustainable Development, “The phosphorus pulses are not trivial. Cumulatively, we’re still putting way too much phosphorus into Lake Winnipeg.”

“The other things we would be concerned about are things like pharmaceuticals, pathogens like E. Coli and then just a lot of organic matter,” she adds. “The more we have these spills, the more we see our downstream waterways compromised.”

The City of Selkirk is, in the words of Mayor Larry Johannson, “the last community on the mighty Red River before the majestic Lake Winnipeg.”

“Everything passes by the city of Selkirk on its way,” Johannson said at a water-related press conference in nearby Lockport in April.

A lifelong Selkirkian, he recalls years where the city hosted waterskiing championships, and years where his family could drink from the water at their Lake Winnipeg cottage. He’s also a member of the International Joint Commission’s Red River Watershed Board and the Red River Basin Commission, both of which work to manage and protect the river across borders. He’s seen the impact of pollution flowing out of Winnipeg firsthand — and he’s vowed to do what he can to repair the waterways.

“There was a time when you were in the middle of Lake Winnipeg and you were fishing, you could put your cup into the water and drink that water,” Johannson says. “I wouldn’t dare do that now, but maybe generations from now we’ll be able to get back to that.”

The lake beaches just north of Selkirk are often closed due to pollution, Johansson says, and it impacts quality of life for those living near the water. “When you have ‘Do not swim in the lake’ every other week because of pollution — that’s not right.”

Selkirk is not the only nearby lake community living with the cumulative impacts of decades of pollution.

In November 2023, the city realized one of two old pipes running under the river near the Fort Garry Bridge in the St. Vital neighbourhood was at risk of failing, so it shut the pipe down for repairs and diverted the sewage flow into its equally outdated twin. The second pipe failed three months later.

More than 230 million litres of raw sewage flowed into the Red River over a period longer than two weeks, marking the second-worst spill in city history.

In response, 11 First Nations downstream of the river and surrounding Lake Winnipeg filed lawsuits worth a combined $5.5 billion against all three levels of government, alleging they have breached Treaty and Charter rights by failing to address Winnipeg’s decades of water pollution. The three suits, originally filed separately, are now being litigated together.

“Treating the Red River and Assiniboine River as part of the sewage system has polluted Lake Winnipeg,” the statement of claim says.

The case is incredibly complex, encompassing discharges from the treatment plants, sewer overflows and emergencies like the 2024 sewage spill over a period of about 20 years. The nations say repeated sewage releases into the river — and the impacts on Lake Winnipeg — have caused health problems, destroyed fisheries, limited access to drinking water, prevented traditional practices and had adverse psychological effects, including a mistrust of the waters. The communities allege they have not been informed when leaks or accidental releases occur, nor has there been meaningful dialogue about the way these leaks and spills impact the First Nations. The 11 nations are bringing the case forward as trustees of the lake, known as Weenipagamiksaguygun, who “has a spirit as a living being.”

”The city has a history of repeatedly violating its environmental licences and having wastewater discharges that are purportedly accidental or unplanned but entirely predictable,” the claim alleges.

“Every discharge of treated or untreated wastewater into the river system, whether planned or unplanned, constitutes a continuous and ongoing breach of duty by the city.”

Mayes believes this suit (alongside Environment Act charges, with fines up to $500,000, laid against the city by the provincial government,) could be key to unlocking a “a bit of urgency” when it comes to sewer system upgrades. The spill prompted the Manitoba government to contribute an extra $10 million to water infrastructure projects.

For its part, the city denies that sewage overflows and spills have damaged the lake or infringed on the First Nations’ rights. In a statement of defence filed in early May, the city said the sewage it releases into the river system has minimal impact on nutrient loading in Lake Winnipeg and is “not responsible for the impacts on the health of Lake Winnipeg.”

“Nutrients and pollutants flowing into Lake Winnipeg come from a variety of sources both inside and outside of Manitoba, including wastewater and surface runoff from large regions of intensive agriculture,” the city said. The Manitoba government’s statement of defence makes similar complaints, though it “acknowledges that the discharge of wastewater from the City’s … combined sewer systems may contribute to nutrient levels and water quality impacts in the river system and the Lake Winnipeg watershed,” but notes it is “challenging to … conclude that one source has had specific impacts on the lake.” The province further said it had fulfilled its duties to monitor and enforce environmental law when it comes to the city’s sewage system, and the responsibility to notify affected communities of a spill falls on the city.

Winnipeg Mayor Scott Gillingham told reporters in February the city plans to make significant investments to “prevent diluted sewage or raw sewage going into our rivers.”

In its statement of defence, the city said it continues to make significant investments to reduce sewage overflows, and has operated a notification system for overflows and other spills since 2004.

The city declined to provide an interview regarding sewer overflows, and did not respond to specific questions from The Narwhal and Winnipeg Free Press, instead pointing to its sewer overflow FAQ page and documents posted on the city website.

Taylor, whose kayaking dock is just downstream of the Fort Garry Bridge where the spill took place, is bolstered by the renewed momentum. Ultimately, he understands the city — even the province — can’t afford to take on the work alone. He believes it’ll take sustained federal investment (rather than the more “ad hoc” funding he’s seen so far) to bring the layers of aging, failing infrastructure up to scratch. And he knows Winnipeg is up against the clock.

“I understand it’s expensive, we can’t afford to do it, but there are other alternatives and there needs to be some resilience built in,” he says, referring to green infrastructure solutions like rain gardens to help reduce runoff, and underground water storage solutions that can mitigate spills. “We’re in the middle of climate change — we have no resilience at all.”

Climate change is projected to result in more frequent storms and heavy rains on the prairies — precisely the conditions that cause overflows.

“This is going to become more and more of a ‘flashy’ system as time goes on, as we see the increasing impacts of climate change,” Kanu, with the Lake Winnipeg Foundation, says.

“I don’t remember rainstorms in the summer that flooded out [under]passes when I was a kid, and I feel like that happens two or three times a year now. Our system isn’t built for what’s happening now — and it certainly isn’t built for what’s coming.”

Canada is facing a looming infrastructure crisis exacerbated by more frequent weather extremes. Accidental sewage spills are often a result of power outages, which the Canadian Climate Institute projects will occur more often under the strain of extreme heat and major storms. As massive rain events become commonplace, so too will inland flooding, which will strain storm sewer infrastructure.

“As we’re seeing more variation in temperature, we’re going to see more water, more precipitation, and potentially larger spring melts,” Roy, with the IISD, says. “These shifts in temperatures mean that we’ll see cracks in pipes and the aging infrastructure will fail us.”

To build some resilience in the urban landscape, stop the flow of harmful pathogens into the city’s waterways and make the rivers something Taylor, Kanu and other residents can proudly enjoy — the city will need to move much faster than planned.

“We should be celebrating our rivers here in Winnipeg. We should be using them and enjoying them,” Kanu says. “They should be a source of joy for us — not a source of fear and contamination.”

Julia-Simone Rutgers is a reporter covering environmental issues in Manitoba. Her position is part of a partnership between The Narwhal and the Winnipeg Free Press.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion